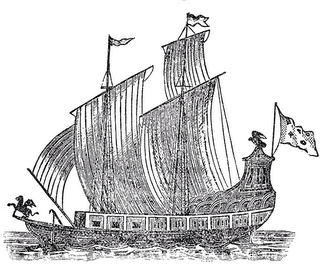

Legendary French explorer Rene-Robert Cavalier, Sieur de LaSalle's flagship, the Griffon the first European vessel to sail the upper

Ever since the loss of LaSalle's Griffon in 1679, the

I found a very informative reference book on ship wrecks around the Great Lakes area, specifically Lake Erie, very well researched by a diving couple, one so full and thick on the shipwrecks deep inside Lake Erie alone, they were forced to split it into two volumes, with a third volume hot off the press very soon. These were titled "Erie wrecks, volumes 1 & 2" . I gave both volumes to Adam for a Christmas gift, mostly for the interesting aspect of them, but also to research and possibly visit someday, being a master diver himself. He loved them.

These vessels are time capsules of a kind that can be found nowhere on land. In addition to giving us a look into the society, technology, culture and artifacts of a bygone century, many of these vessels give an eerie picture of the horrific and desperate last moments of a ship and crew who knew they were likely to die. It is a startling realization that a short 150 to 200 feet under nearby waters lay many remarkable archeological resources which are largely undiscovered.

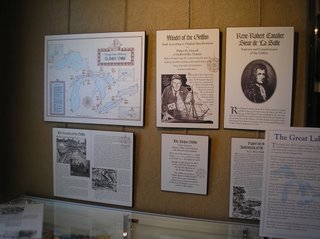

Recently one of our day trips took us to

Steve Libert, president of Great Lakes Exploration Group, LLC, has an obsession for exploration. National Geographic may have been credited for the phrase “Exploration is an Obsession”, but it was certainly inspired by someone like Libert. "Human progress depends on exploration and discovery,” he says. “And I think individual explorers still have an important role to play.” He himself has been researching “The Griffon” for over 28 years and is now suing the state of

The fact that the Griffon was built in the wilderness, as opposed to a shipyard, will reveal the circumstances

The Voyage of the Griffon

The Griffon’s maiden voyage started from

The Griffon sailed from what is known today as

While researching LaSalle's great "Griffon" after seeing the artifacts within the small town museum, I came upon a website of the "Great Lakes Shipwreck conservation program" and again, my interest peaked.

Read the following excerpts, take a second look at the artifacts in the case above in the photos I snapped, then let me know what you think. Personally it would be a momentous occasion to be the finder of a sunken ship, sure to be treasured by all who explored for it. However on the flip side, after reading about the conservation program's purpose, and remembering the artifacts above came deliberately from "diver looters" in a way, I'm all for leaving them well preserved in depths of the water!

And there you have it folks, leave them as is, right where they are!

Because the widespread availability of SCUBA is a relatively recent phenomenon, many historic and legendary vessels have yet to be discovered or disturbed. Most shallow wrecks that are easily accessible have already been damaged by waves and ice. Vessels deeper than 100 feet, however, are likely to be in excellent shape and are less likely to be found without an intensive search. Thus, many divers have taken up wreck hunting and new historical wrecks are being found every year. As sport divers become more comfortable in the 100 to 250 foot depth range, more and more discoveries will be made. The increasing availability of technology such as side scan sonar and the popularity of tech diving also insure that more wrecks will give up the secret of their locations.

The discovery of new wrecks is perhaps a positive and unavoidable eventuality. However, what happens to these wrecks is not. Experienced divers always relate stories of what a fantastic dive a wreck was "before she was stripped." In fact, just about every wreck that has been found in the Great Lakes has a collateral story of some artifacts that were stolen from it. Too often, naive divers are lured with stories of "treasure" to plunder wrecks. The hard truth is that most Great Lakes wrecks contain nothing even remotely resembling gold or silver. Divers find only "semi-precious" artifacts of an historical nature which they remove from the vessel and stick in the corner of their garage where no one else can view them. Wooden artifacts soon begin to rot no matter how much care is taken with them, as was the case with the 150 year old schooner Alvin Clark that was raised from Green Bay in 1969. She was destroyed after her metal parts cracked and she rotted into the ground. History has clearly shown the futility of removing artifacts from Great Lakes shipwrecks. Further, because the removal of artifacts from Great Lakes shipwrecks is illegal, most of these items are never seen again and rarely find their way to museums for proper conservation.

As the diving community in the Great Lakes has grown, many people have become staunch advocates of wreck conservation. The State of Michigan took a leading role when it established the Underwater Preserve system. These preserves ensure that wreck stripping and plundering will be kept to a minimum and that violaters will receive harsh penalties. Organizations such as Preserve Our Wrecks, Save Our Shipwrecks and others take an active role in conservation by regularly inspecting local wrecks to insure proper conservation. Other divers ensure conservation simply by letting their diving friends know that they will not dive with looters and even by reporting people who display artifacts to them.

There is also questionable validity in bringing artifacts to the surface for display in museums. Many nameboards have been taken off the sterns of wrecks and are now on the walls of museums and displays. Chadburns, binnacles, capstans, wheels, propellers and rudders have all been removed and placed in foreign environments where they look awkward and tell us little about their vessels. On land, these items often appear to be rusty and rotted pieces of junk. Aboard the ship however, these items have a great significance. They convey a greater sense of the vessel's historical nature and give clues as to its final moments and ultimate demise. Artifacts are also likely to last longer in the cold waters of the Great Lakes than anywhere else. There are already enough shipwreck artifacts in museums and displays to sate the appetite of the non-diving public. The artifacts of new shipwreck discoveries should be left in state for those interested enough to don a wetsuit.

Recently, the Alger Underwater Preserve sank an old harbor tug within its waters as a dive attraction. This tug which wouldn't have garnered a snapshot from even the most ardent marine historian now brings thousands of divers to Munising each year, generating hundreds of thousands of tourism dollars. However, on dry land one of the oldest and most historic wrecks on the Great Lakes, the Alvin Clark, couldn't even generate enough interest to keep her from the bulldozer. Clearly, these facts speak for themselves.

For these reasons divers in the Great Lakes region need to take action to further establish and maintain bottomland preserves and conservation organizations in all five Great Lakes and surrounding states and provinces. Perhaps by these means, there will still be some historical wrecks left worth diving in 50 years.

.jpg)